Why the New Kamehameha Schools Lawsuit Might Be Over Before It Starts: A Guide to “Standing”

If you’ve been following the news, you know that Students for Fair Admissions (SFFA) just filed another lawsuit against Kamehameha Schools on October 20, 2025. This is the third attempt to challenge the school’s Native Hawaiian admissions preference in federal court, and if you’re thinking “didn’t we already do this twice?”—you’re right. But here’s the thing: this new lawsuit might not even make it past the starting gate, and understanding why requires understanding one of the most fundamental (and often frustrating) concepts in American law: standing.

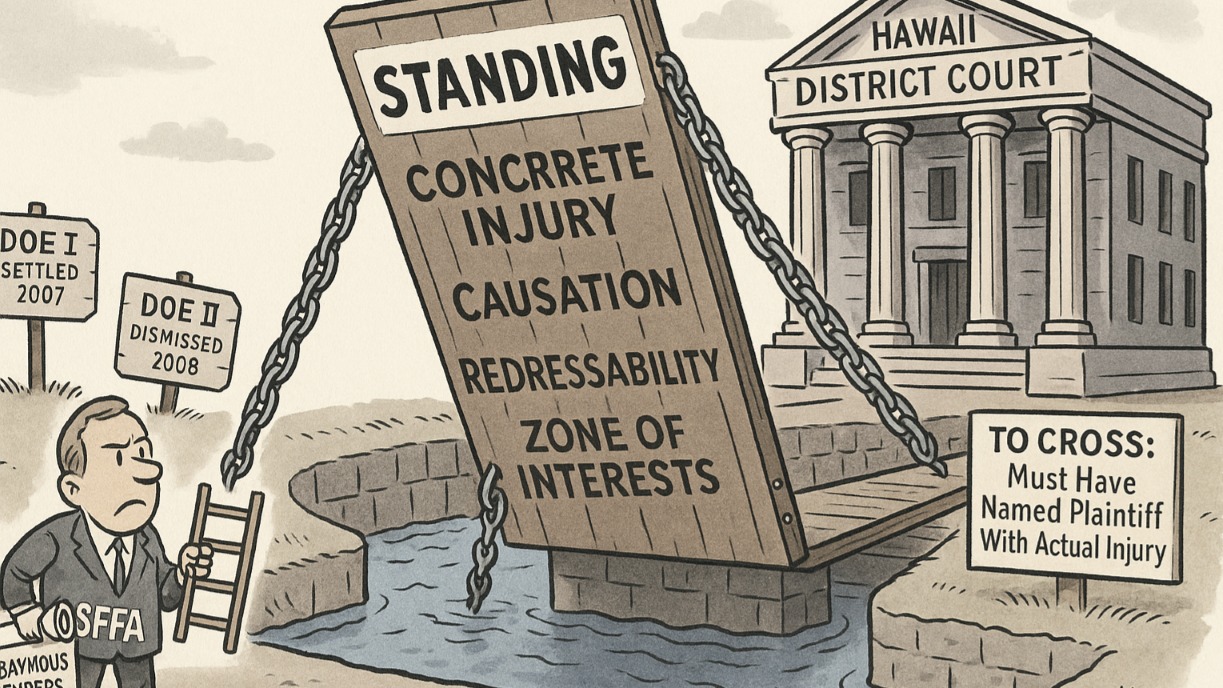

What Exactly Is “Standing” and Why Should You Care?

Here’s the deal: you can’t just walk into federal court and complain about something that bothers you. You can’t sue because you think a law is unfair, or because you disagree with how an organization operates, or even because you genuinely believe someone is being wronged. Federal courts aren’t advice columns or philosophy forums. They only have the power to resolve actual disputes between real parties who have genuinely been harmed.

Standing is the legal gatekeeper that ensures only people with real, concrete problems can use the courts. Think of it like this: if you tried to file a police report because your neighbor’s house got burglarized, the police would say “that’s not your house—your neighbor needs to file the report.” Standing works the same way in court.

This isn’t just legal red tape. It comes from Article III of the U.S. Constitution, which limits federal courts to deciding actual “cases” and “controversies.” The Founders didn’t want federal judges acting as roving problem-solvers or issuing advisory opinions about hypothetical situations. They wanted courts deciding real disputes between actual people.

The Three Core Requirements: Harm, Causation, and Redressability

To have standing, you need to satisfy three basic requirements. Let’s break them down in plain English:

1. Harm (or “Injury-in-Fact”)

You must have suffered an actual injury. Not a hypothetical future injury. Not an injury to someone else. Not a philosophical objection. An actual, concrete harm that has happened or is certainly about to happen to you.

In the Kamehameha context, this would mean: “I applied to Kamehameha Schools, I was qualified, but I was rejected because of my race.” That’s a concrete harm. It happened to a specific person at a specific time.

What’s NOT a concrete harm? “I generally oppose racial preferences in education.” That’s an ideological position, not an injury. Or, “Someone, somewhere might want to apply to Kamehameha someday and might get rejected.” That’s too speculative.

The injury also has to be particularized—meaning it affects you specifically, not just everyone in general. If a law raises everyone’s taxes by $5, you might argue that’s your particularized $5 injury. But if you’re just upset that the government is spending money unwisely in general, that’s too diffuse. Courts call these “generalized grievances,” and they’re not enough for standing.

2. Causation (or “Traceability”)

Your injury must be traceable to the defendant’s conduct. There must be a clear line from “what they did” to “the harm you suffered.”

For example: “I was rejected from Kamehameha Schools, and the school’s policy explicitly gives preference to Native Hawaiian applicants. I am not Native Hawaiian. Therefore, the policy caused my rejection.”

What wouldn’t work: “I was rejected from Kamehameha Schools, but I don’t know why. Maybe it was my grades, maybe it was my essay, maybe it was the racial preference policy.” That’s too speculative. You need to show that the defendant’s specific action caused your specific harm.

3. Redressability

If you win your lawsuit, the court must be able to fix your problem. This is called redressability—can the remedy you’re seeking actually redress (fix) your injury?

In a Kamehameha case, this would mean: “If the court strikes down the racial preference policy and orders the school to reconsider my application without considering race, that would remedy my injury.”

What wouldn’t work: “I want the court to declare racial preferences wrong in principle, even though I never applied to Kamehameha and never plan to.” Even if the court issued that declaration, it wouldn’t fix any injury you suffered, because you didn’t suffer one.

These three requirements—harm, causation, and redressability—are constitutional requirements. If you don’t meet them, federal courts literally don’t have the power to hear your case, no matter how right you might be on the merits.

The Fourth Piece: Zone of Interests (Prudential Standing)

Beyond these constitutional requirements, courts also apply what are called “prudential” standing rules—judge-made doctrines that further limit who can sue. The most important one for this case is the zone of interests test.

Here’s what it means: even if you’ve been harmed, you can only sue if your injury falls within the “zone of interests” that the law was meant to protect. You can’t piggyback on someone else’s legal rights.

Let me give you an example. Imagine a law says “employers cannot discriminate against employees based on race.” If you’re an employee who was discriminated against, you can sue—that law was designed to protect you. But what if you’re a competing business owner, and you’re upset because your competitor is discriminating and therefore might be getting better employees? You might have an economic injury, but you’re not in the zone of interests. That law was designed to protect employees from discrimination, not to protect competitors from competition.

In the context of civil rights laws like Section 1981 (which prohibits racial discrimination in contracts), the zone of interests is clear: the law protects people who want to make contracts but are denied equal treatment because of their race. It protects the person being discriminated against.

Here’s where it gets tricky for SFFA: if no actual person who was rejected from Kamehameha is willing to put their name on the lawsuit, can an organization sue on behalf of anonymous members? And more importantly, is SFFA really vindicating their members’ interests in attending Kamehameha, or is SFFA pursuing its own organizational interest in eliminating race-based admissions policies nationwide?

That’s the zone of interests problem. SFFA has a stated mission: to challenge race-conscious admissions policies. That’s their whole purpose. But Section 1981 wasn’t designed to protect advocacy organizations pursuing ideological goals. It was designed to protect individual people who faced discrimination when trying to make contracts.

How the Previous Kamehameha Lawsuits Failed on Standing

This isn’t SFFA’s first rodeo with Kamehameha, and it’s not even the first time standing has been an issue. Let’s look at what happened before.

Doe I (2006-2007)

The first lawsuit against Kamehameha’s admissions policy was filed by a student using the pseudonym “John Doe.” The case actually went to trial, and Kamehameha paid a settlement to make it go away. Interestingly, Kamehameha didn’t object to the pseudonym in that case. The student was a minor, and everyone seemed fine with protecting his identity.

Doe II (2007)

After settling the first case, another group of parents quickly filed a second lawsuit—this time with multiple John and Jane Doe plaintiffs. But this time, Kamehameha objected to the pseudonyms. And the district court agreed.

The court held that Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 10(a) requires parties to use their real names. The rule is pretty simple: “The title of the complaint must name all the parties.” The court found that using pseudonyms violated this rule, and dismissed the case.

Now, there are exceptions. Courts sometimes allow pseudonyms when there are extraordinary circumstances—cases involving sexual assault victims, cases where disclosure would risk severe harassment, cases involving minors in particularly sensitive matters. But the Doe II court found that the plaintiffs hadn’t met that high bar, especially since the families could still apply to Kamehameha even after suing, and because Hawaii has many other educational options.

The Ninth Circuit affirmed the dismissal. The message was clear: if you want to challenge Kamehameha’s policy, you need to put your name on the lawsuit.

SFFA’s Strategy in the New Case: Clever, But Probably Doomed

So here’s where the October 2025 lawsuit gets interesting. SFFA clearly learned from Doe II. They know they can’t have anonymous plaintiffs. So they tried something different.

In this new case, Students for Fair Admissions is the only named plaintiff. They’re not using pseudonyms—SFFA is using its real organizational name. The two families (which the complaint calls “Families A and B”) are described not as “plaintiffs” but as “standing members” of SFFA whose situations establish that SFFA has associational standing to sue.

See the distinction they’re trying to make? The complaint argues: “Rule 10(a) prohibits parties from using pseudonyms. But Families A and B aren’t parties—they’re just members of SFFA. SFFA is the party, and SFFA is using its real name. So there’s no Rule 10(a) problem!”

It’s creative. It might even be too clever by half.

The Associational Standing Problem

Organizations can sometimes sue on behalf of their members. This is called “associational standing,” and it’s how groups like the NAACP have been able to bring important civil rights cases. The requirements are:

- The organization’s members would have standing to sue in their own right

- The interests at stake are germane to the organization’s purpose

- Neither the claim nor the relief requires participation of individual members

SFFA is trying to use this doctrine. But here’s the catch-22:

To prove element #1—that their members would have standing—SFFA needs to show that Families A and B have suffered concrete injuries from Kamehameha’s policy. They need to show these families are real, that they actually want to attend Kamehameha, that they would actually apply, and that they would actually be rejected because of race.

But how can the court verify any of that if the families remain anonymous?

Think about it:

- Does Family A actually exist, or is this a hypothetical?

- Have they actually applied and been rejected, or is this speculative?

- Are they genuinely interested in Kamehameha, or did SFFA recruit them just for this lawsuit?

- Are they actually non-Hawaiian, or could they qualify under the preference?

The court can’t answer these questions without knowing who these families are. And if the court can’t verify that the members have standing, then SFFA can’t have associational standing.

It’s like saying “I represent injured people, so I should be able to sue on their behalf” while refusing to identify any actual injured people or prove they were injured. The court is going to say: “Show me the injured people, or you don’t have a case.”

The Zone of Interests Problem (The Real Killer)

But there’s an even bigger problem, and this is where that fourth standing requirement—zone of interests—comes in.

Let’s be clear about what SFFA is. According to its own complaint, SFFA is “a nonprofit membership organization whose mission is to support and defend students who are discriminated against on the basis of race or ethnicity in education.” That’s their stated purpose. They exist to challenge race-based admissions policies.

Now ask yourself: whose rights is SFFA really trying to vindicate here?

If Families A and B won’t put their names on the case, if they won’t publicly assert their own rights, if they won’t accept the consequences and potential backlash that comes with challenging a beloved Hawaii institution—then how important is attending Kamehameha to them, really?

Section 1981 protects people who want to make contracts and are denied equal opportunity because of their race. But the people who want those contracts—the families who want their kids to attend Kamehameha—aren’t willing to step forward and say “this is important enough to me that I’ll put my name on it.”

Instead, you have an advocacy organization whose entire purpose is challenging racial preferences, trying to use anonymous members as vehicles to pursue the organization’s own ideological goals.

That’s the zone of interests problem. SFFA isn’t really vindicating their members’ interests in attending Kamehameha. They’re vindicating SFFA’s interest in eliminating race-conscious admissions policies. And that’s not what Section 1981 was designed to protect.

The complaint itself kind of gives the game away. It spends pages and pages talking about threats and harassment directed at Edward Blum (SFFA’s president) and about SFFA’s website and SFFA’s mission. It reads more like “SFFA is being attacked for its advocacy work” than “these families desperately want their children to attend Kamehameha.”

Courts are going to notice that.

The Harassment Issue: Real, But Not Enough

Now, let’s address the elephant in the room. The complaint devotes significant space to documenting threats and harassment. And look, let’s be absolutely clear: the threats described in the complaint—death threats, antisemitic slurs, violent rhetoric—are inexcusable. No one should face that kind of hatred for filing a lawsuit, regardless of how you feel about the merits.

But here’s the hard truth about standing: those threats don’t change the legal analysis.

Think about it this way. If someone is attacked by a gang, and they want to sue the gang, it’s reasonable to assume they might face retaliation or threats. That’s a real and serious concern. But the victim still has to make a choice: “Is this important enough to me that I’m willing to face those consequences and assert my rights?”

If the answer is yes, they move forward—hopefully with appropriate protection and support. If the answer is no, that’s understandable too. No one should be forced to put themselves in danger.

But what you can’t do is have a third party—who isn’t the victim—step in and say “I’ll sue on behalf of this person, but I won’t tell you who they are.” That’s not how standing works.

The threats and harassment are a separate matter. People making threats should face legal consequences for their actions. But the existence of threats doesn’t eliminate the requirement that someone who wants to challenge Kamehameha’s policy must be willing to step forward and assert their own rights.

This is a fundamental principle: you must be willing to accept the consequences of your actions. If getting your child into Kamehameha is genuinely important enough to challenge their admissions policy in federal court, then you need to be willing to put your name on that challenge. Not have someone else do it for you while you stay hidden.

Courts have allowed pseudonymity in truly extraordinary cases—sexual assault victims, people who would face physical danger from government actors in repressive regimes, children in sensitive custody disputes. But “people might say mean things about me” or “my community might disapprove” generally doesn’t meet that extraordinarily high bar, especially when there are other good schools available and when the families haven’t even been rejected yet.

Why This Case Is Likely to Be Dismissed Quickly

Put it all together, and you can see why this case is on shaky ground:

-

Verification Problem: The court can’t verify that Families A and B exist, have concrete injuries, or meet the standing requirements, because they’re anonymous.

-

Ripeness Problem: According to the complaint, these families haven’t actually applied to Kamehameha yet. They’re pre-emptively suing over rejections that haven’t happened. That’s speculative—not the kind of concrete, imminent injury required for standing.

-

Zone of Interests Problem: SFFA is pursuing its organizational mission to eliminate race-conscious admissions, not truly vindicating individual members’ interests in attending Kamehameha.

-

Rule 10(a) Evasion: The court could easily view this as an end-run around the clear holding in Doe II. The substance is the same—anonymous parties challenging Kamehameha—it just has extra structural steps.

-

The “Standing Member” Dodge: SFFA’s argument that Families A and B aren’t “parties” so Rule 10(a) doesn’t apply is too cute. If these families’ injuries are essential to establishing standing, they’re effectively parties in all but name.

Kamehameha’s lawyers are undoubtedly already drafting a motion to dismiss on standing grounds. And they have a pretty strong argument.

But This Doesn’t Mean the Issue Goes Away

Here’s the thing: even if this case gets dismissed on standing grounds (which seems likely), that doesn’t mean SFFA or others can’t try again. The legal pathway is actually pretty clear: find someone willing to put their name on the complaint.

If a non-Hawaiian family actually applies to Kamehameha, actually gets rejected, and is actually willing to publicly challenge the policy in court using their real names, that would solve the standing problem. They would have:

- A concrete injury (actual rejection)

- Clear causation (the racial preference policy caused the rejection)

- Redressability (an order to reconsider without racial preferences would fix the injury)

- No zone of interests problem (they’re asserting their own rights, not a third party’s)

The question is: can SFFA find such a family?

The Practical Reality

And here’s where we need to be honest about the situation: they probably can’t.

Hawaii isn’t like the mainland. Kamehameha Schools isn’t just another private school. For many in Hawaii’s Native Hawaiian community, Kamehameha represents something profound—a legacy of Princess Bernice Pauahi Bishop, an institution dedicated to improving the lives and wellbeing of Native Hawaiian children, a connection to culture and heritage that was nearly destroyed by colonization.

For a non-Hawaiian family living in Hawaii to publicly challenge Kamehameha’s admissions policy would be seen by many in the community as an attack on Native Hawaiian culture itself. The social consequences would be severe. The backlash would be real. And yes, some of that backlash has crossed the line into threats and harassment (which is unacceptable).

But that’s also precisely why standing matters. The law requires that the person asserting the right be willing to step forward and accept what comes with it. You can’t sue anonymously because you don’t want to deal with the consequences. And you can’t have an advocacy organization from Virginia sue on your behalf while you stay hidden.

If no one in Hawaii is willing to step forward and publicly challenge Kamehameha’s policy, that tells you something important: either people don’t think it’s worth the social cost, or the harm isn’t significant enough to them to warrant taking that step.

And that’s actually how standing is supposed to work. It ensures that only people with real, significant, concrete injuries use the courts. If the injury isn’t significant enough for someone to attach their name to it, maybe it’s not the kind of concrete injury federal courts should be addressing.

What Happens Next?

Here’s what you can expect:

-

Motion to Dismiss: Kamehameha will file a motion to dismiss on standing grounds, probably within the next few weeks.

-

SFFA’s Response: SFFA will argue that they have proper associational standing and that Rule 10(a) doesn’t apply to them.

-

The Court’s Decision: The district court will have to decide whether SFFA’s structural workaround solves the problems identified in Doe II, or whether it’s just the same issue with extra steps.

My prediction? The court dismisses the case on standing grounds. The reasoning would be something like: “You can’t establish associational standing based on anonymous members whose injuries we can’t verify, and even if you could, you’re not in the zone of interests because you’re pursuing your organization’s goals rather than your members’ individual rights.”

-

Appeal: SFFA would likely appeal to the Ninth Circuit, arguing that the district court got the standing analysis wrong.

-

Back to Square One: Even if SFFA loses on appeal, they could try again with a named plaintiff. But good luck finding one.

Why Standing Matters More Than Ever

Some people find standing doctrine frustrating. “Why all these technical barriers?” they ask. “Why can’t we just decide if Kamehameha’s policy is legal or not?”

But standing isn’t just a technicality. It’s a fundamental feature of our constitutional system. It ensures that courts decide real cases involving real people with real injuries, not abstract policy debates or ideological crusades.

In this case, standing is doing exactly what it’s supposed to do: it’s asking “whose rights are really at stake here?” If it’s Families A and B, then they need to step forward. If they won’t, then maybe those rights aren’t being violated in a way that’s concrete and significant enough to warrant judicial intervention.

And if it’s really SFFA’s rights that are at stake—their right to challenge racial preferences as a matter of organizational mission—well, that’s not what civil rights laws like Section 1981 were designed to protect.

The Bottom Line

The new SFFA lawsuit against Kamehameha Schools faces an uphill battle before it even gets to the merits of whether racial preferences in admissions are legal. The standing problems are significant:

- Anonymous “standing members” whose injuries can’t be verified

- Possible lack of ripeness (no actual applications or rejections yet)

- Zone of interests issues (SFFA pursuing its own organizational goals)

- The appearance of evading the clear holding in Doe II

Could SFFA overcome these problems? Maybe, if they have a very sympathetic judge. But the smart money is on dismissal.

The path forward for anyone who genuinely wants to challenge Kamehameha’s policy is clear: apply to the school under your real name, accept rejection if it comes, and file suit as yourself. Not through an organization. Not anonymously. You, personally, asserting your rights.

That’s what standing requires. That’s what the Constitution requires. And that’s why this third attempt to sue Kamehameha Schools will likely end the same way the second one did—dismissed before it really begins.

The question that remains is whether anyone will ever be willing to take that step. And if the answer is no, then perhaps that tells us that the injury—while possibly real in principle—isn’t concrete enough in practice to warrant federal judicial intervention.

That’s standing. That’s how it works. And that’s why this lawsuit is probably over before it starts.